Welfare reform and rent risk: why tenants fall into arrears and what can be done

Last year we developed a Universal Housing Form to support housing providers; a pre-tenancy affordability and benefit check to protect both tenant and housing provider from preventable, unsustainable tenancies.

Since then, housing providers have told us about a drop in early arrears development, enhanced understanding of the welfare system, and better relationships with their tenants.

Understanding income sources for low-income families is crucial to sustainable tenancies. But with the welfare policy landscape moving as fast as it is, what do housing providers need to know in order to boost trust, secure rent payments, and support the health and wealth of their tenants?

This article provides a run through of our recent research and analysis specifically to support housing providers taking a whole-systems approach to working with the communities they serve. We cover:

- how sanctions and deductions have changed to impact rent shortfalls

- how income fluctuations impact Universal Credit payments

- how changes to disability benefits may bring future disruption and what we can do about it

More than half of all tenants are paying debt directly from their benefits

For housing providers, rent arrears are often seen as a tenant issue. But our research shows the problem is often built into the system itself. Knowing and understanding this can support more holistic engagement with tenants.

For housing providers, rent arrears are often seen as a tenant issue. But our research shows the problem is often built into the system itself. Knowing and understanding this can support more holistic engagement with tenants.

Our report for Lloyds Bank Foundation reveals that over half of all low income households on Universal Credit are repaying debt directly from their benefit awards, before a single pound reaches their bank account. For those in receipt of disability or carer-related elements in Universal Credit, that figure rises to six in ten.

Over the period of the study, these deductions eroded household incomes by up to a quarter, creating rent shortfalls even in otherwise stable tenancies.

From April 2025, the government introduced a new “Fair Repayment Rate” that lowered the cap on deductions from 25% to 15% of the standard UC allowance. While welcome, this change doesn’t go far enough. It ignores the fact that many households are hit by multiple simultaneous reductions, including the bedroom tax, Local Housing Allowance shortfalls, the two-child limit, and the benefit cap.

As a result of these multiple reforms, families with the highest barriers to work—single parents, carers, and households with disabled children—are the most likely to experience unsustainable financial pressure, despite being in receipt of entitlements designed to support them.

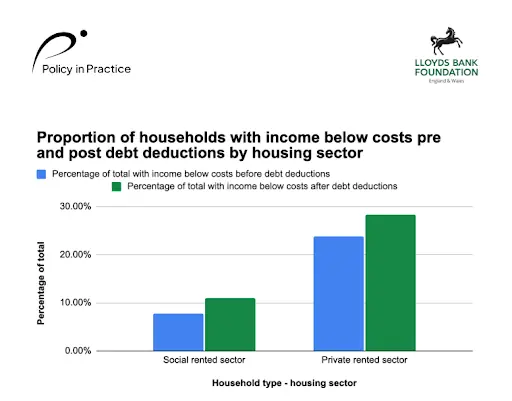

Alongside these demographic risks, housing provider type matters too with clear links to private sector unaffordability; something front line advisors can support with income maximisation.

Lastly, sanctions add a further layer of risk. Though fewer households are affected, those that are can lose up to 100% of their UC standard allowance, with little to no financial buffer. These are not abstract policy effects; they’re direct contributors to missed rent, arrears escalation, and, in the worst cases, homelessness.

Housing providers have told us that early intervention like the use of the Universal Housing Form helps pre-empt these pressures by ensuring ALL benefits are being claimed, not just Universal Credit.

The volatility trap: Why take-home income can’t always be trusted

When tenants fall into arrears, it’s often, and often grossly unfairly, attributed to poor budgeting, or underemployment. But our research shows another culprit: erratic income patterns conflicting with Universal Credit design.

In our analysis of over 70,000 Universal Credit households for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, we found that among working tenants, 36% see a month to month impact on their UC awards because their income fluctuates, sometimes by just a few pounds.

In our analysis of over 70,000 Universal Credit households for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, we found that among working tenants, 36% see a month to month impact on their UC awards because their income fluctuates, sometimes by just a few pounds.

Universal Credit is designed to respond to income changes in real time. But this real-time design means small changes in income can cause disproportionately large changes in support, on a frequent basis, particularly when pay dates don’t align with assessment periods. In fact, about 1 in 6 households experience volatility solely because their pay day doesn’t match their UC cycle.

The result? One month’s lower income isn’t reflected in higher UC until the next month delaying the ability to pay routine bills. And that delay matters when rent is due, food needs buying, or direct debits bounce.

Housing providers see the downstream effects: rent shortfalls, arrears, and broken tenancies, caused not by poor choices, but by a benefit system that behaves unpredictably for those with the least room for error.

While housing providers can’t change their tenants’ paydays, they can ensure income from all available sources has been factored into rent relationships. Securing and shoring up tenancies with income maximisation tools means fewer tenants need to consider rent v’s other priority bills when the money they have to spend is different every month.

Read more about income volatility and its impact on other services

Disability benefit reforms: A new risk factor for tenancy stability

For housing providers, the stability of tenancies is closely tied to the financial security of tenants. Upcoming reforms to disability benefits will introduce new challenges that may undermine this stability, particularly for those already facing financial hardship. Getting to grips with income maximisation now can shore up low-income family budgets ahead of potential cuts.

Our analysis shows the government’s proposed changes to disability benefits are set to affect approximately 2.9 million people, with an estimated £6.8 billion in support at risk.

These reforms include:

- Tightening eligibility for Personal Independence Payment (PIP), potentially disqualifying individuals who do not score at least four points in any one daily living activity

- Halving the rate of the Universal Credit health element for new claimants and freezing it for existing claimants until 2029/30

- Scrapping the Work Capability Assessment, making PIP the gateway to receiving the UC health element

These changes are expected to have a disproportionate impact on certain regions. The North East, Wales, and the North West are projected to be the hardest hit, both in terms of the number of people affected and the financial impact.

For instance, in the North West, nearly 430,000 people are expected to be affected, with over £1 billion lost from incomes and local economies as a result. And with the potential to see increased rent arrears and potential evictions, the demographic for those on housing waiting lists and in temporary accommodation is likely to shift to include more disabled people than ever before.

For housing providers both in and outside these regions, these reforms could lead to:

- Increased rent arrears as tenants lose a significant portion of their income

- Higher demand for support services as tenants struggle to navigate the new system and manage their finances

- Greater risk of tenancy breakdowns, particularly among vulnerable groups such as single parents and individuals with mental health conditions

It’s crucial for housing providers to proactively engage with tenants who may be affected by these changes, offering support and guidance to help them navigate the new system and maintain their tenancies.

Find out more about the potential impact of these reforms in your area

Register now to learn more about the impact of these changes on local authorities

Create more sustainable tenancies with income maximisation

Our award winning Better Off platform is being used today by housing providers to get ahead of arrears, ensure their tenants are maximising their incomes, and crucially, improving relationships.

Major housing provider, the Northern Ireland Housing Executive, has generated more £3.5 million in additional income for their tenants with more than £850,000 added to rent accounts using the Better Off platform. These aren’t small amounts, this is financial support direct to your tenants, fewer evictions, and increased trust.

We helped our social housing clients identify, on average, over £6,800 per year in unclaimed benefits for each person who was missing out.

Our research into the welfare state and its impacts informs the inner workings of our Better Off platform ensuring we’re not only up to date, but that we’re getting ahead of the major changes, risks, and relationships affected by national policy at the local level. For the housing sector, understanding the welfare-to-rent pipeline is crucial for tenants, community health, and bottom line rent collection.

Book a call with our team to find out how your housing team can best use these tools.