Are UK cities overdue a dose of devolution?

“If the citizens of New York, Frankfurt and Tokyo can be trusted with tax-raising powers, why not the people of London, Greater Manchester or the North East?”

Clive Betts, Chairman of The Commons Communities and Local Government Committee

In the first of two blogs, Policy in Practice gives an overview of the journey to devolution in Britain to date. This journey is now at a turning point as local elections on Thursday 4 May give voters from six English Combined Authorities the chance to directly elect ‘metro mayors’ with significant powers, for the first time. We highlight the opportunities this could bring for cities, authorities and LEPs to revolutionise public services and ensure inclusive economic growth.

Through our work with over 40 Local Authorities across Britain, Policy in Practice understands how local nuances are affected by national policy, and how local support needs to be tailored and targeted to each individual household. The transfer of more powers to local and regional authorities can be a significant step towards ensuring this.

In part 2 we consider how local organisations can ensure that devolved funds are properly invested in addressing the area’s unique issues. Our webinar on tracking the incomes and employment situations of low income households on Wednesday 24 May will show what this can look like in practice.

Devolution to Britain’s cities: what, why, where and when?

Devolution refers to the transfer of powers over financing and decision-making from central to more local government entities. This gives local government the ability to join up public services, adapt policy to local contexts and, in some cases, manage tax collection and revenues. In recent years, devolution from Britain’s central government to its cities has gathered pace, with devolved government increasingly seen as a way to encourage local innovation in public service delivery and allow cities or local areas to become financially more self-sustaining.

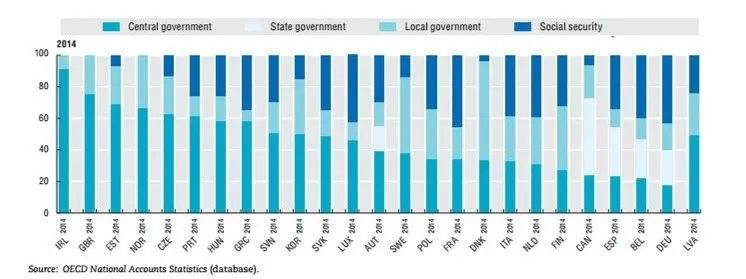

Figure 1: Distribution of government spending among levels of government, 2014

In terms of government spending, Britain is among the most centralised countries in the developed world. As the graph above shows, over 75% of all British government spending in 2014 went through central government, second only to the Republic of Ireland. By comparison, in countries like Spain, Belgium and Germany, central government is responsible for less than 25% of expenditure.

In light of this, and especially given the current context of a growing economic divide between London and the rest of the country, there are growing calls for more spending to be devolved and give struggling cities more opportunities to catch up. According to data from the ONS , London’s gross value added (GVA) per person stood at £43,629 in 2015, representing almost 23% of the total UK economy. This compares to a UK-wide figure of £25,351 and just £18,927 in the North East of England. Also, research by the Resolution Foundation suggests that this gap has actually widened since the financial crisis, with all city regions bar London still below their pre-crisis GVA per person levels.

City-regions understand their specific situations better than central government does, the argument goes, so devolution can be a tool to close down the gap between London and other cities and deliver more equitable economic growth for the whole of the Britain. The economic realities facing British cities are complex and varied, so a one-size-fits-all approach isn’t the best way to bring lagging British cities up to London’s performance. Instead, there is a growing, cross-party consensus that cities and city-regions should be empowered to address specific skills and employment shortages, assess their own infrastructure and service needs and support local industries, plus lots more.

There is some robust evidence that decentralisation as an economic policy delivers positive returns. For the UK specifically, IPPR North believes that regional discrepancies in public spending on skills, transport and research and development under the current system of central government grants is holding back growth in the North and Midlands. Infrastructure spending, for example, stood at £215 per person per year in London and the South East, compared to £135 for the North of England (even when ‘big ticket’ items such as Crossrail or Thameslink are taken out of the equation) . It follows, then, that if non-London cities are given more control of their finances, they might choose to close this north-south gap in infrastructure spending, especially as more investment in transport, skills and R&D can play a crucial role in attracting private investment and jobs.

The journey of UK devolution, so far

In the past decade, there have been three broad processes of devolution from central government to cities. These are City & Growth deals, the creation of Combined Authorities and devolution to the Greater London Authority.

2012: The Local Growth Fund and Cities / Growth deals for 8 core cities

City and Growth deals, agreed in the coalition government, are an initiative to devolve specific packages of funding for public services and flexibilities for specific programmes and outcomes. Funding comes from the ‘Local Growth Fund’, which totaled over £2bn in 2015/2016. The first ‘wave’ of City/Growth deals were signed by the eight Core Cities (Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham and Sheffield) in July 2012.

2014: Cities/Growth deals for all LEPs

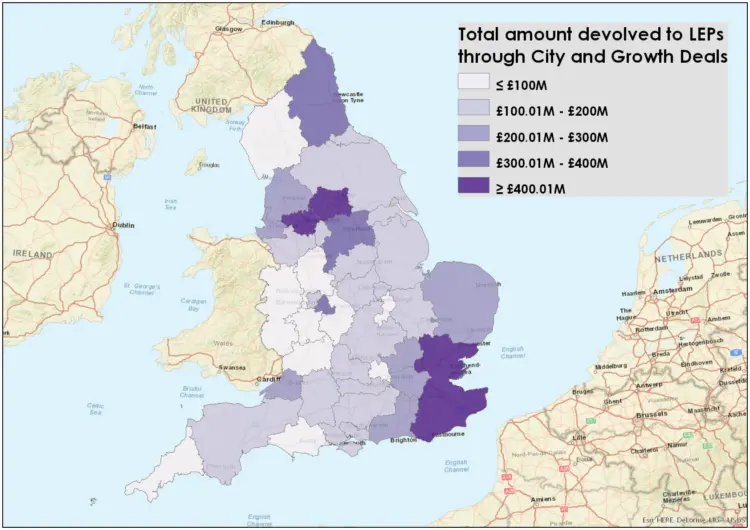

By July 2014, the government had agreed Cities/Growth Deals with each of the 39 Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs). Figure 2 shows the total amount of funding devolved to LEPs as of March 2016, which totals over £7.3bn . Leeds City-Region and Greater Manchester lead the pack, having received over £0.5bn each in devolved funding to date. The 2016 Autumn Statement confirmed a further £1.8bn to be awarded through Cities and Growth deals.

Figure 2: Distribution of City & Growth deal funding, by LEP

2016: Combined Authorities come of age

Combined Authorities (CAs) were originally introduced in the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act of 2009. They allow local areas/authorities that are particularly integrated (typically if they are part of a broader urban conurbation) to create a combined administrative area, not too dissimilar from the Greater London Authority (GLA). So far, there are nine in the UK (seven of which are English Core Cities ). However, it was not until further legislation was enacted in 2016 that the legal framework for devolution deals to be struck with CAs was in place, setting the ground for bespoke devolution deals to be thrashed out between government and CAs.

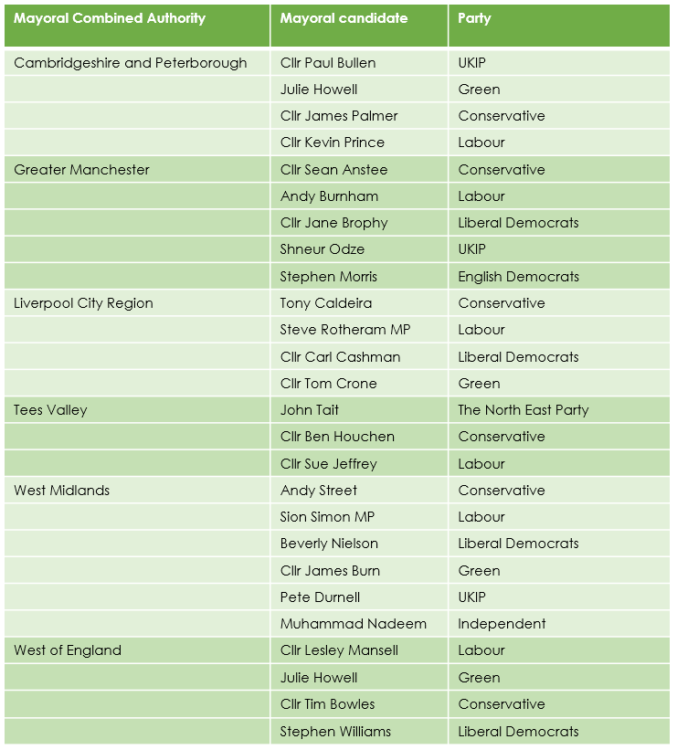

The process of becoming a CA gives an area the option to directly elect a ‘metro mayor’. Six CAs (Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, Tees Valley, West Mildlands and West of England) will be the first to directly elect a mayor in the 2017 local elections, see Figure 3 for the May 2017 Mayoral Election Candidates. The Act also paves the way for the devolution of other powers in a more ad-hoc fashion. For example, Greater Manchester Combined Authority, arguably the most advanced CA, will have the budget for the Work and Health Programme (estimated to be worth £20-£25million) devolved from the Department for Work and Pensions, and is in conversations with HM Treasury over future devolution of transport funding.

Figure 3: List of May 2017 Mayoral Election Candidates

The Greater London Authority – an exception

The process of devolution is more developed in London than in any other region of the UK. The Greater London Authority, established in 2000, is the most significant effort to devolve power to London. The GLA gives London an elected mayor and powers over transport, policing, economic development, and fire and emergency planning. The GLA will also have control over its share of the Work and Health Programme, plus an affordable housing settlement worth £3.15bn to build 90,000 homes by 2020-2021.

Where next?

The devolution agenda is likely to continue in the following years, as more City/Growth deals are awarded to specific LEPs and Combined Authorities negotiate the ad-hoc transfer of more powers and budgets. The six “metro mayors” being elected in next month’s local elections, and the extent to which they are successful in both winning new powers for their cities and ensuring that these translate into equitable economic growth, will serve as a good litmus test for how far devolution in Britain has come in the last decade.

One further point for negotiation will likely be the devolution of property tax revenue streams – including council tax, stamp duty, land tax and business rates – with the ability to reform those taxes while retaining prudential rules for borrowing, similar to recent changes in Scotland. This would provide stable and continuous funding to stimulate economic growth according to local needs, allowing cities to raise sustained investment for vital infrastructure such as transport, schools, housing, energy supply and technology.

In part two …

We consider how local organisations can ensure that devolved funds are properly invested in addressing an area’s unique issues. We show how administrative household level data collected by Local Authorities can be used to identify households that are vulnerable or are at risk of poverty, and take a look at how Croydon Council is using their insights to drive economic growth in their area.

- Read Using household-level data to understand the drivers of poverty in London, supported by Trust for London