Making the most of Universal Credit: financial incentives

Last week the Resolution Foundation launched its report, Making the Most of UC, which is the result of a nine-month review of Universal Credit led by a panel of experts.

Similar to Policy in Practice’s review of Universal Credit, it aimed to take the focus off the delivery timetable and IT problems that have plagued UC, and examine the key underlying policy choices instead.

The report calls Universal Credit one of the ‘biggest, boldest and riskiest’ of the coalition government’s welfare reforms with ‘entirely honourable’ intentions.

But, like any welfare system, Universal Credit needs to balance trade-offs between the cost of the system, the level of support offered, and the incentives provided to enter and progress in work.

This post will focus on financial work incentives, comparing Policy in Practice’s own review of Universal Credit by highlighting broad areas where we agree and also where Policy in Practice thinks there is a better way forward.

The Context: Persistent Low Pay

The trade-offs within Universal Credit were addressed when the policy was designed in 2010, at a time when the government’s focus was on economic recovery after the downturn. Many policy levers within Universal Credit were aimed at reducing worklessness.

But five years on, the number of workless households is now at an all-time low and the economy has seen impressive jobs recovery.

Meanwhile, one in five workers are on low pay and two thirds of children in poverty live in working families.

Low pay is a persistent problem. Only one quarter of those with low hourly wages in 2001 managed to permanently move onto higher pay a decade later.

The key challenge Universal Credit should be tackling, the report argues, is therefore in-work poverty and progression in work.

Comparing Work Incentives Under Both Systems

Universal Credit aims to get more people into work by improving financial incentives.

Under the current system, work incentives can be relatively weak. As we demonstrated in our review of Universal Credit, the withdrawal of benefit can lead to people losing most, or in some cases all, of their increased earnings from work.

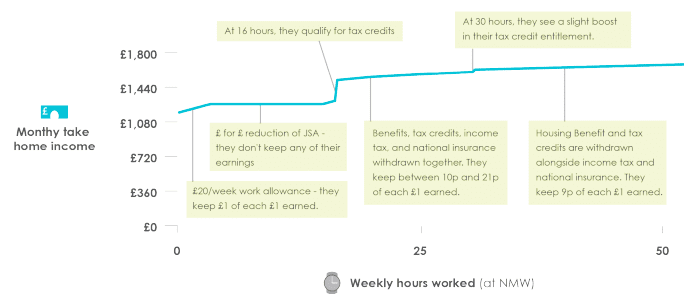

Below is an example for a lone parent. It shows how their take home income would increase under the current system the more hours they worked. A flatter line indicates weaker work incentives.

To address this problem, Universal Credit provides:

- A simpler withdrawal of benefits that is easier to understand

- A higher work allowance which allows people to keep more of their earnings before any UC is withdrawn

- A lower withdrawal rate compared to income-replacement benefits like Jobseeker’s Allowance

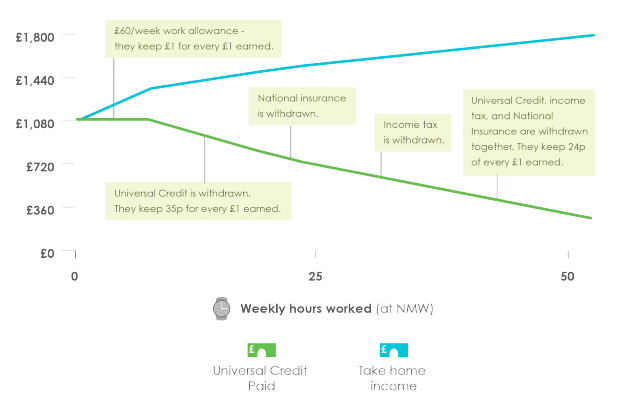

The figure below is an example for the same lone parent under Universal Credit. The person gets to keep more of their earnings from work under UC – with the maximum they will lose being 76p for each pound.

How Motivational Is The Work Allowance?

The work allowance under Universal Credit is much more generous than the current system, but the Resolution Foundation recommends adjusting it to focus support where they believe it will have the biggest impact.

Under the current system, our lone parent example above has a strong incentive to work at least 16 hours, the point at which they are eligible for Working Tax Credit. They would see a big jump in income if they did.

Under Universal Credit, while work incentives are smoother, there is no clear number of working hours that is most advantageous.

The Resolution Foundation report is concerned that this may cause some groups to reduce, rather than increase, the number of hours they work. The fall in their earnings would lead to a higher Universal Credit award, and ultimately a bigger welfare bill.

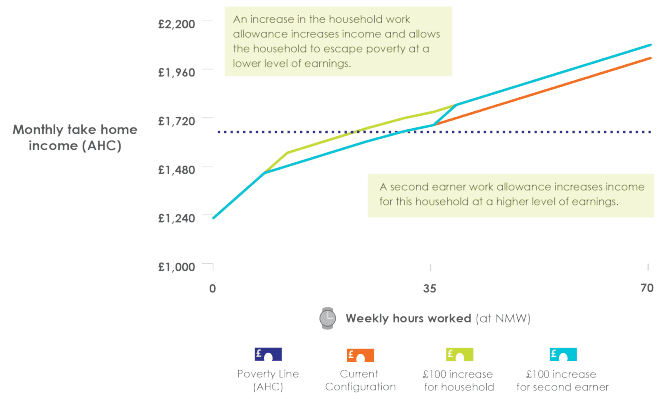

Given scarce resources, The Resolution Foundation seeks to use the work allowance where it will have the biggest impact. They recommend that the government:

- Increase the work allowance for single parents (because they may otherwise be incentivised to reduce their hours)

- Introduce a second earner work allowance (because they will see their work incentives worsen under Universal Credit)

- Reduce the work allowance for couples with children (because both partners are out of work in only 1 in 10 couples)

- Remove the work allowance for non-disabled single people without children (because their work incentives have already improved under UC)

In contrast, Policy in Practice have argued that a second earner work allowance would benefit those on relatively higher incomes, since one partner is already in work.

We advocate an increase in the household work allowance for all household types so that everyone in work would benefit, including those on the lowest earnings.

What Is The Best Withdrawal Rate?

Universal Credit has a withdrawal rate of 65%. This means that for each pound a person earns, they will lose 65p of their Universal Credit and see a 35p increase in their total take home income. When income tax and National Insurance withdrawal is added to this, Universal Credit recipients only keep around 24p per pound earned.

For many people, particularly those receiving multiple benefits, this withdrawal rate will be an improvement on the current benefit system. However for some middle to high income households receiving only tax credits, which have a withdrawal rate of 41%, work incentives will actually decrease.

The Resolution Foundation supports lowering the withdrawal rate of Universal Credit in the longer term, as funds allow. A 55% withdrawal rate, as originally suggested in the Centre for Social Justice’s report Dynamic Benefits, would ensure that no one would see their financial incentives worsen under Universal Credit.

Policy in Practice’s review of Universal Credit also recommended that the withdrawal rate be reduced, ideally to 55%. We argue that this change would:

- Support a large number of working households on low incomes

- Increase incentives to progress in work

- Help other measures, such as increasing the minimum wage, become more beneficial to people receiving Universal Credit

However, the Resolution Foundation’s report points out that there is little evidence to show what the most effective withdrawal rate would be. They therefore recommend extensive randomised control trials to determine the most effective taper rate for UC. Policy in Practice supports this recommendation, and hopes that it will be taken up by the Department for Work and Pensions.

Policy in Practice also believe that the saliency of work incentives will be important to making Universal Credit and other welfare reforms work. Our Universal Benefit Calculator has been shown to communicate the impact of moving into work in a fast, visually engaging way.

To view a bite sized demo of Policy in Practice’s Universal Benefit Calculator click here >

The Impact of Income Tax on UC

Universal Credit is calculated based on a household’s net income, meaning that changes in the amount of income tax that someone pays directly affects their UC award.

As I have written in the past, this means that increases in the personal allowance which are popular with politicians don’t benefit people receiving Universal Credit as much as they benefit those on higher earnings, no longer in receipt of Universal Credit.

If the personal allowance for income tax were increased by £100, basic rate taxpayers not on Universal Credit would see their net earnings increase by £20, but those on Universal Credit would see an increase of just £7.

Around six in ten Universal Credit recipients would not benefit from the change at all, either because they are out of work or already earning below the threshold.

The Resolution Foundation recommends addressing this issue by making an equivalent adjustment in the work allowance any time the changes are made to tax rates or allowances.

While this recommendation would help to make sure people receiving Universal Credit benefit equally from tax changes, it increases public spending by failing to challenge the use of the tax system to improve the lives of people on low incomes.

Changes to the tax system are expensive and affect those on relatively higher earnings. Policy in Practice therefore argues that government should use Universal Credit instead of (rather than in addition to) the tax system if they want to support low income households.